Corey Barksdale, oil on canvas, n.d.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Guernica

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Medium: oil on canvas

Date: c. 1937

One of Picasso’s best known works, Guernica is Picasso’s critique of the German bombing raid of a little Basque village in northern Spain. As Germany gears up for war, Adolph Hitler, with the approval of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, chooses the village of Guernica as a site for bombing practice. On April 27th, 1937, the unsuspecting hamlet is pounded with high-explosive and incendiary bombs for over three hours. Townspeople are cut down as they run from the crumbling buildings. Guernica burns for three days. Sixteen hundred civilians are killed or wounded.

By May 1st, news of the massacre at Guernica reaches Paris, where more than a million protesters flood the streets to voice their outrage in the largest May Day demonstration the city has ever seen. Eyewitness reports fill the front pages of Paris papers. Picasso is stunned by the stark black and white photographs. Appalled and enraged, Picasso rushes through the crowded streets to his studio, where he quickly sketches the first images for the mural he will call Guernica.

Prior to the bombing, Picasso had been commissioned to create the centerpiece for the Spanish art exhibition at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. Three months later, Guernica is delivered to the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris Exposition. Almost prophetically, the Spanish Pavilion stands in the shadow of Albert Speer’s monolith to Nazi Germany. The Spanish Pavilion’s main attraction, Picasso’s Guernica, is a sober indictment of the tragic events in Spain.

After the Fair, Guernica tours Europe and Northern America to raise consciousness about the threat of fascism. From the beginning of World War II until 1981, Guernica is housed in its temporary home at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, though it makes frequent trips abroad to such places as Munich, Cologne, Stockholm, and even Sao Palo in Brazil. The one place it does not go is Spain. Although Picasso had always intended for the mural to be owned by the Spanish people, he refuses to allow it to travel to Spain until the country enjoys “public liberties and democratic institutions.”

Described as modern art’s most powerful anti-war statement, Guernica is seen as an amalgamation of pastoral and epic styles. Guernica is a mural-size canvas (3.5 m (11 ft) tall x 7.8 m (25.6 ft) wide) painted in oil. The somber palate of blue, black and white intensify the drama, producing a stark, almost photographic record of the tragedy. The meaning of key figures – a woman with outstretched arms, a bull, an agonized horse – are left open to one’s interpretation. When asked for their symbolic meaning , Picasso replied “A painting is not thought out and settled in advance. While it is being done, it changes as one’s thoughts change. And when it’s finished, it goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it.”

Urban Folk Art

Corey Barksdale, untitled, oil on canvas, n.d.

Abstract Collage

Corey Barksdale, untitled, oil on canvas, n.d.

Panel 23

Panel 59

Panel 35

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park

Artist: Diego Rivera

Medium: Fresco mural located in Mexico City

Date: c. 1947

In Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park, hundreds of characters from Mexico’s history gather for a stroll through Mexico City’s largest park. The mural is a surrealist scene, complete with historical personages, which portrays 400 years of Mexican history. Read from left to right, the mural chronologically progresses from the conquest and colonization of Mexico (left), to the Mexican Revolution (center) through to the modern era (right). Prominent figures represented in the mural include: Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conqueror who initiated the fall of the Aztec Empire; Sor Juana, a seventeenth-century nun and one of Mexico’s most notable writers; Porfirio Díaz, whose dictatorship at the turn of the twentieth century inspired the Mexican Revolution; and President Benito Juárez, who restored the republic after French occupation.

The center scene of the mural has been described as a snapshot of bourgeois life in 1895 Mexico — refined ladies and gentlemen promenade in their Sunday best, under the watchful eye of Porfirio Díaz in his plumed military garb. One gets a sense of the inequality which stirred Mexican commoners to overthrow the dictatator Porfirio Díaz and establish their independence.

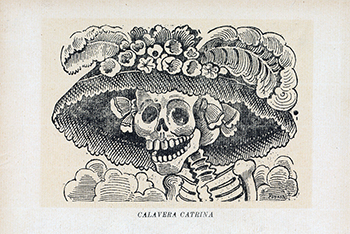

The centerpeice of the mural is a self portrait of Rivera, standing with his wife, artist Frida Kahlo, printmaker and draughtsman, José Guadalupe Posada, and Posada’s Catrina Skeleton character. Catrina was a slang term in early Twentieth Century Mexico, to describe an elegant, upper-class Mexican woman who dressed in European fashion.

Posada’s depiction of La Catrina as a skeleton was understood to be a critique of the Mexican elite. Rivera adorns La Calavera Catrina with an elaborate boa necklace, representative of the feathered Mesoamerican serpent god Quetzalcóatl.

José Guadalupe Posada, La Calavera Catrina, etching, 34.5 x 23 cm, c. 1913

More often than not history is written by the victor and thus reflects an incomplete story. Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park is the antithesis of this: Rivera gives voice to the the forgotten indigenous population normally edited from the historical record by telling their story through his grand narrative. The artist reminds the viewer that the struggles and glory of four centuries of Mexican history are due to the participation of Mexicans from all strata of society.

Essay by Doris Maria-Reina Bravo

(Edited by Lawrence Christopher Skufca)

Louie Armstrong

Corey Barksdale, Louie Armstong, Street Art, n.d.

Buhdda Brothers

Corey Barksdale