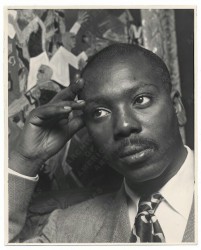

Norman W. Lewis (1909-1979) was a Black American painter, of Bermudan descent, associated with the Harlem Renaissance and the Abstract Expressionist movement. Lewis was a member of the tight-knit Harlem artistic community, known as the 306 Group, which included prominent African American artists such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence. Continue reading Norman Lewis

Category Archives: Racial Equality

Miguel Covarrubias

Miguel Covarrubias was a Mexican artist who is best known for his work as an illustrator, writer, and anthropologist. Covarrubias’ style was highly influential in America, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, and his artwork and caricatures of influential politicians and artists were featured on the covers of The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. Covarrubias’ artwork displayed his keen interest in anthropology and cultural studies. Continue reading Miguel Covarrubias

Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was an American painter, associated with the Harlem Renaissance and the Social Realist Movement. Lawrence forged a unique and original art form, combining the tempera technique (pigment mixed with a binder consisting of egg yolk thinned with water) with a cubist style. All of his work was unmistakably modern, but remained within the conceptual framework of realism and figurative painting. Lawrence referred to his style as “dynamic cubism,” though by his own account the primary influence was not so much the French tradition, so much as the shapes and colors of Harlem. Continue reading Jacob Lawrence

Lois Mailou Jones

Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998) was an American abstract-expressionist painter associated with the New Negro Movement. Jones’ numerous oils and watercolors incorporating African and Hatian motifs are her most widely recognized works. Jones’ mastery of the principles of Cubism, her affinity for bright colors and her unique ethnic style have proven to have an enduring appeal. Continue reading Lois Mailou Jones

Archibald John Motley, Jr.

Archibald John Motley, Jr. (1891-1981) exemplifies the cultural diversity within the American modernist art community known as the New Negro Movement. Motley is best known for his colorful chronicling of the African-American experience during the 1920s and 1930s, depicting a vivid, urban black culture that bore little resemblance to the conventional and marginalizing rustic images of black Southerners which were common during this era. Continue reading Archibald John Motley, Jr.

Into Bondage

Aaron Douglas, oil on canvas, c. 1936

Into Bondage premiered as one element of a four-part mural series in the Hall of Negro Life at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. It was Douglas’ intention to create and present fresh, modern images depicting the contributions of African Americans to the state’s history and achievements. This painting portrays slavery, as Douglas believed that understanding the past was essential to moving forward in the future.

The bound captives descend toward two large ships that are set to transport the Africans across the Atlantic to their future of enslavement. While most of the men’s heads are bowed low in despair, the woman on the left looks up and raises her shackled hands above the horizon line.

The large central figure’s eye slit recalls the masks of the Dan people of Africa. His profiled head and chest and twist of the hips demonstrate Douglas’ predilection for ancient Egyptian art. Although the man stands on a pedestal referencing the auction block from which he will be sold, a ray of light from the North Star, which guided slaves on the Underground Railroad, illuminates his face and foreshadows his ultimate freedom.

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas (1898-1979) was the Harlem Renaissance artist whose work best exemplifies the New Negro Movement. Douglas was an active member of the thriving cultural milieu known as the New Negro Movement which sought to cultivate the Black American cultural experience and highlight the effects of racial injustice. Progressive at heart, he developed a distinctive painting style using silhouetted forms and fractured space to express both, the harsh struggles of African American life in 1920’s Harlem and the future hope of social progress. Continue reading Aaron Douglas

The Evolution of Equality in America

A Comparative Analysis Between the Lincoln and Jeffersonian View of Racial Equality

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” [1].

With these words, Abraham Lincoln impressed his vision of racial equality upon the American political landscape, effectively supplanting the limited Jeffersonian concept of human equality based on natural right and the utility of “moral sense.” [2].

Lincoln envisioned an equality of the races, both, politically and socially, which ventured far beyond Jefferson’s simple premise of equal treatment under the law. Lincoln understood racial equality to be based upon natural, as well as, sacred right. [3]. He attributed the intellectual differences among men to be due to the “doctrine of necessity”– men’s intellect being guided “by some power,” outside of their control [4], rather than strictly being the product of biology or education.

For Lincoln, all men are created equal meant all of mankind, not just Whites of European descent. Thus, Lincoln’s sense of equality was more inclusive than Jefferson’s. While Lincoln was careful not to denigrate Negros as necessarily being physically, mentally, nor morally deficient, he was also careful not to enrage the dominant class by publicly conceding racial equality, acknowledging “he is not my equal in many respects – certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowments.” [5].

Lincoln saw Negros as being capable of making an intellectual contribution to society. In a private letter to Michael Hahn, Governor of Louisiana, Lincoln wrote:

Now you are about to have a Convention which, among other things, will probably define the elective franchise. I barely suggest, for your private consideration, whether some of the colored people may not be let in-as, for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks. They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom. [6].

Jefferson felt otherwise; he conceded that Negros might be morally equal to the Whites, but saw them as physically and intellectually inferior. According to Jefferson, nature had provided “distinctions” between the races; besides the physiological differences, blacks lacked “forethought,” proper “reason,” and were “much inferior” in intellect. [7]. For these reasons, Negros, if emancipated, were to be segregated to prevent a “mixing of the races.” [8]. Jefferson was victimized by the poor science of his day, the prevailing European theory of Phrenology posited that Negros had a smaller brain mass than Whites.

Jefferson’s equality was contingent on natural rights. All men were not “created equal” with natural attributes; each was endowed with differing degrees of “talent” and “virtue,” – thus, each was afforded the right to pursue prosperity on an equal footing, but were unequal in their ability to attain the same level of achievement. [9]. Nevertheless, all men were equal in their natural right to procure “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” and they shared a common “moral sense,” of “right and wrong” provided by nature. [10]. Jefferson upheld that by exercising this intrinsic quality, through education, all men were capable of coming to a consensus on “self-evident” truths such as these.

Lincoln’s views on morality differed, in that they were based on his doctrine of necessity, rather than the Jeffersonian understanding of an internal moral sense. For Lincoln, educated men could come to opposing positions on the same issue, for “the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control.” [11]. Lincoln’s later writings support the notion that he may have believed this vague external force to be the result of God exercising his sovereign will in different circumstances to meet His divine plans and purposes. [12].

One of the great moral truths both, Lincoln, and Jefferson, could agree on was the injustice of the subjugation of the African race. Jefferson wrote:

The love of justice and the love of country plead equally the cause of these people, and it is a moral reproach to us that they should have pleaded it so long in vain, and should have produced not a single effort, nay fear not much serious willingness to relieve them and ourselves from our present condition of moral and political reprobation. [13].

Lincoln echoed these sentiments:

The monstrous injustice of slavery itself . . . Deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world-enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites- causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty. [14].

Where Lincoln veered from Jefferson was on the source of the natural right to equality. Lincoln appealed to the common humanity of the Negro, in His assertion that “it is your own sense of justice, and human sympathy, telling you, that the Negro has some natural right to himself … will you ask us to deny the humanity of the slave?” [15]. Lincoln also contended slavery was a transgression of the natural right to self-governance “according to our ancient faith,” and that “the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed.” [16]. He agreed that this was intrinsically understood, not by nature, but by divine ordinance. Furthermore, Lincoln argued that “the relation of masters and slaves is Protanto, a total violation of this principle.” [17].

Jefferson and Lincoln concurred on the premise of a slave’s right to equal treatment under the law. Jefferson asserted that “whatever be their degree of talent it is no measure of their rights” [18], while holding onto the future hope for the Negro’s “re-establishment on an equal footing with the other colors of the human family.” [19]. Lincoln was even bolder in his stance, asserting “there is no reason in the world why the Negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence.” [20]. Lincoln avowed that the Negro, “in the right to eat bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns… is my equal… and the equal of every living man.” [21].

Lincoln’s greatest innovation was in transforming Jefferson’s abstract intellectual principle of equality into a concrete moral imperative. While treading lightly, Lincoln sought to replace Jefferson’s equality of nature, with an equality of status. In Lincoln’s opinion, the question was not “can any of us imagine better?” but rather, “can we do better?” [22]. Lincoln’s major obstacle was that “the great mass of white people” was reluctant to embrace the ideal of social and political equality between the races. Despite his lack of public support, Lincoln endured, and patiently nurtured the seeds of racial equality that Jefferson had so carefully sown. However, it would take another century before those seeds would begin to bear fruit.

Lawrence Christopher Skufca (2007)

Some Rights Reserved

Bibliography

[1] Lincoln, Abraham. Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Cemetery at Gettysburg, November 19, 1863. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 735.

[2] Jefferson, Thomas. Moral Sense. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 72.

[3] Lincoln, Abraham. The Repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the Propriety of its Restoration: Speech at Peoria, Illinois, In Reply to Senator Douglas. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 302-304.

[4] Lincoln, Abraham. Religious Views: Letter to the Editor of the Illinois Gazette. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 187-188.

[5] Lincoln, Abraham. First Debate, at Ottawa, Illinois, August 21,1858. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 445.

[6] Lincoln, Abraham. Letter to Governor Michael Hahn, March 13,1864. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 745.

[7] Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia, queries XIV and XVIII. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 48-49. Stable URL: http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch15s28.html

[8] Ibid., p. 50.

[9] Jefferson, Thomas. The Natural Aristocracy. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 75-79.

[10] Jefferson, Thomas. Moral Sense. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 72.

[11] Lincoln, Abraham. Religious Views: Letter to the Editor of the Illinois Gazette. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 187-188.

[12] Lincoln, Abraham. Meditation on the Divine Will. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 655.

[13] Jefferson, Thomas. Emancipation and the Younger Generation. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 91-92.

[14] Lincoln, Abraham. The Repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the Propriety of its Restoration: Speech at Peoria, Illinois, In Reply to Senator Douglas. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 291.

[15] Ibid., pp. 302-303.

[16] Ibid., p. 304.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Jefferson, Thomas. The Negro Race. Coursepack. Greenville: LAD Custom Publishing, Inc. 2007: 61.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Lincoln, Abraham. First Debate, at Ottawa, Illinois, August 21,1858. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: 445.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Lincoln, Abraham. Message to Congress, 1862. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. Editor: Roy P. Basler. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1946: